Race day nutrition

One of the most challenging aspects of racing or competing is race day nutrition. I have helped many racers process their endurance competition that ended much worse than it started. Even though we will never truly know for sure, nutrition and/or hydration is often the most likely cause.

There are many different types of races and competitions. Each with different feeding strategies. Pre race nutrition is essential for any type of competition or duration. Nutrition during a race will have very little effect shorter races such as durations of 30-60 minutes. The focus of this article will focus mostly on races or events lasting longer than 90 minutes. This article will provide sure fire ways to make sure you have proper nutrition during the day of your race.

First off, In order to avoid runners gut or slosh belly do not overdo the intake of carbohydrates and do not attempt to eat new foods, drink new drinks or take new powders. This is often a fatal flaw to the success of a person’s race day. One thing to be aware of, is the fact that each person absorbs carbohydrates at different rates. Like many things in sports performance, this is trainable. The normal range of absorption is between 40 – 80 grams per hour. Most people can handle 40 grams (160 calories), but a person can adapt to absorb up to 80+ grams (320+ calories) per hour.

One other consideration is whether or not a person is a “carb burner”. During low intensity exercise people should utilize fats as their primary fuel source. Unfortunately, converting fats to usable energy is a slow process. As intensity increases and the need for energy increases, the utilization of carbohydrates increases as well. The quicker we burn through our glycogen stores the more dependent we are on fueling during a race. The most efficient people will utilize fats as the primary fuel source with heart rates as high as 140-150 BPM. While running a metabolic efficiency test, I have seen some “carb burners” that utilize carbohydrates as their predominant fuel source at rest. The consequence of being a carb burner is a higher requirement for fueling during a race. A side note: Heart rate is a direct indicator of effort/intensity. As intensity increases so does heart rate.

DAY MORNING OF THE RACE

In my opinion the hardest challenge is figuring out when to eat before a competition. This is decision is personal and based on the individuals digestive system. The last thing you want to do is look for a porta potty or hide behind a tree to evacuate your bowels during the race. That being said, eating before a long race is essential for three main reasons.

1. Liquids alone generally do not provide proper nutrients.

2. Eating a breakfast will provide the stomach something to digest whereas liquids will move quickly to the small intestines. This will provide satiety throughout the early part of a race. Hunger will start to affect a persons performance.

3. A person has a minimal calorie requirement at rest to perform basic metabolic processes. A person will burn calories from their last feeding until the morning that will need to be replenished.

The general recommendation is to eat 3-4 hours prior to the competition. This may require a person setting an alarm to wake up eat some overnight oats, a few hard boiled eggs and a pint of blueberries that is all washed down with an electrolyte drink such as Nuun tabs or Pedialyte sport.

SUMMARY

EAT A MEAL 3 – 4 HOURS BEFORE RACE

MIGHT NEED TO GET UP EAT & GO BACK TO BED

ALLOWS FOR PROPER ABSORPTION

ALLOWS FOR FOOD TO BE CLEARED FROM GUT

HIGHER IN CARBS (STARCHY PREFERRED)

DON’T TRY NEW FOODS NOW. EAT WHAT YOUR BODY KNOW

ONE HOUR BEFORE RACE

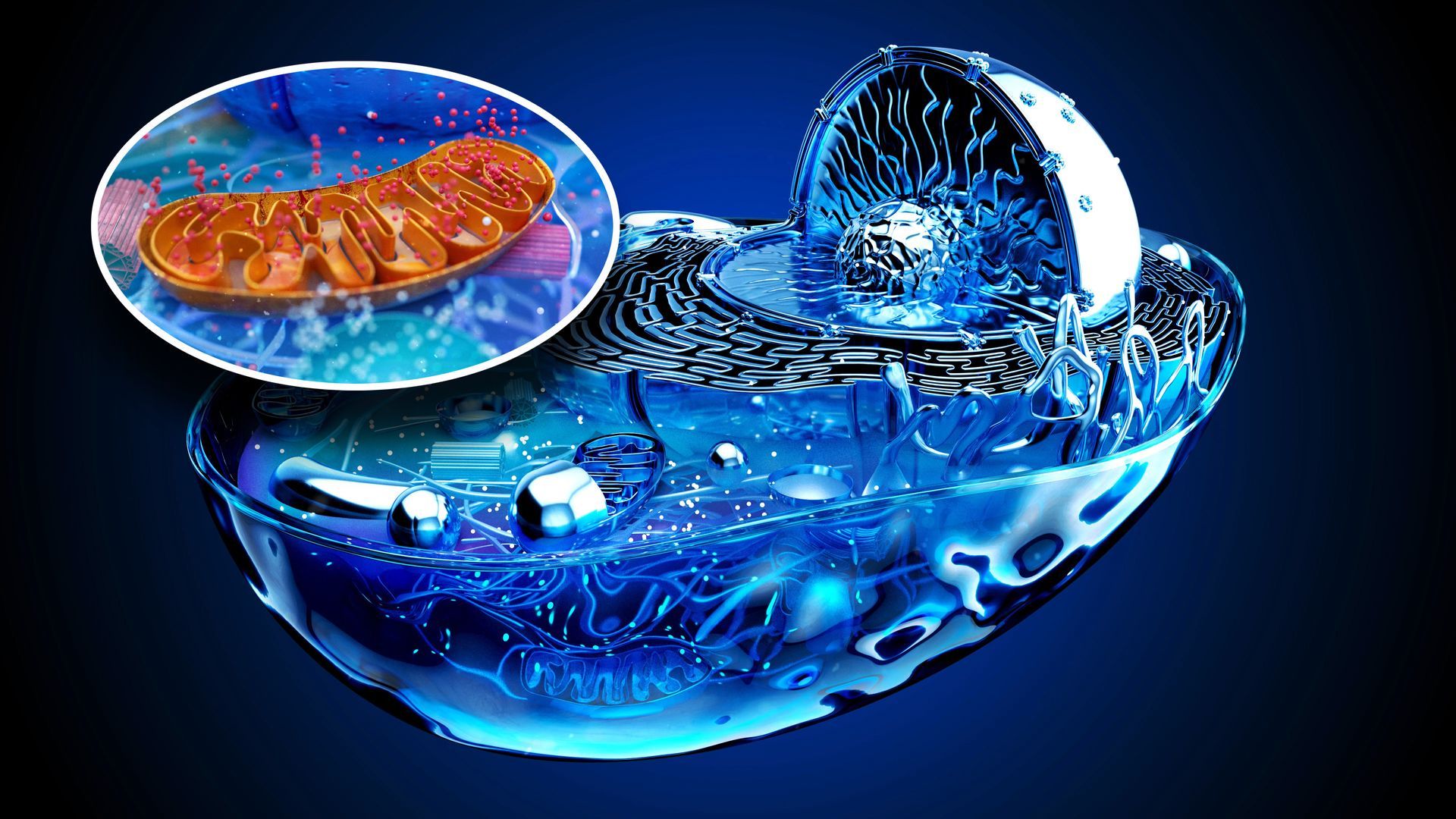

In order for glucose to enter cells, it is transported by a hormone called insulin. When a person consumes sugar insulin is produced by the pancreas and released into the blood stream. This allows glucose to enter the cells. When a person has an insulin spike they will also have a dip in blood glucose. Starting a race with low glucose levels will cause a poor start. In order to avoid this consuming simple carbs 60 minutes before the race will allow the insulin levels to return to normal while the body’s glucose stores to be as close to full as they are going to get. Some people will also consume carbohydrates 15 minutes before a race to maximize their blood glucose. While this is an option and usually effective, you may either absorb it too quickly causing your insulin levels to rise quickly or you may absorb the sugars too slowly, causing the sugars to be stuck in the small intestines. When this occurs, you will feel bloated and possibly feel like you should have used the toilet one last time.

Exactly what to consume 60 minutes before a race will really depend on how long you expect to be out on the course. If your expected finish time is 2 – 3 hours, you may be fine with only a full spectrum carbohydrate food like a banana and sweet potato mash. Just remember with food, what goes in must come out. You may also attempt to use a drink like Cytomax or Karbolyn. If your race is going to be over 3 hours, you will want to eat a full spectrum snack such as beef jerky and a peanut butter & banana sandwich (or 2).

If you choose not to eat before a long race you more than likely will end up feeling hungry at some point during the race. For example, racers of the Tour De France frequently consume homemade rice cakes, small sandwiches with meat, pastries and meal replacement bars.

SUMMARY

- 20 -50 G OF CARBS (FATS & PROTEINS – NOT NECESSARY BUT OKAY)

- DON’T UP THE CARBS HERE PAST WHAT YOU HAVE TESTED

- EXCESS CARBS END UP CAUSING DIARRHEA

DURING THE RACE

Most of our sugar is stored in the liver and muscles as the form of glycogen. Depending on a person’s preparation, each person will have between 60 – 120 minutes of store glucose (glycogen). A person should start dosing their glucose 45 minutes into the race. This early dose will allow the sugar to enter the bloodstream before the body runs out. If possible each dose should be between 15-20 grams every 15-30 minutes. Single doses of 40-80 grams are possible, but may cause a large water amount of water to enter the gut. The reason behind this is water is hygroscopic meaning it attracts water. Absorption of glucose is driven by a concentration gradient. If you have more sugar in your small intestines, then water will move from the blood stream to the small intestines. A large quantity of water in the gut will cause gastrointestinal distress.

SUMMARY

- 30 -60 G OF CARBS PER HOUR

- FATS & PROTEINS ARE NOT ESSENTIAL, BUT OKAY(THE CANNOT BE UTILIZED AS ENERGY)

- SPREAD IT OUT OVER THE HOUR IF POSSIBLE

- FIRST DOSE: 45-60 MINUTES

- STORED CARBS WILL BE DEPLETED IN 1-2 HOURS (NO DEFINITE ANSWER)

AFTER THE RACE

While post-race nutrition will not have an effect on the outcome of the race, it will affect your recovery. Post-race nutrition is especially important for those that will be racing the following day. At this a well-balanced meal should be consumed that consists of ample carbs and proteins. Fats should not be avoided but should be kept to approximately 25% of the caloric intake.

In terms of timing, the first feeding should be within one hour of the finish. The rationale for this is to eat within the anabolic window. The anabolic window is a theory that the body can super absorb carbohydrates and proteins within 1-2 hours post exercise. While this theory is impossible to prove, you are going to eat, so you might as well start eating within the hour. In the summary of this section you will find recommendations for dosing proteins and carbohydrates.

In terms of how many calories you need to eat for recovery, this should be 100% of the calories burnt during the race minus the calories consumed. You will need a VO2max test In order to know how many calories you burn during exercise.

SUMMARY

CARBS RIGHT AFTER RACE

- CHO:PRO – 3:1 OR 4:1 RATIO

- 125 LBS – 50G CHO/15-20G PRO

- 170 LBS – 75G CHO/20-30G PRO

- PROTEIN WILL HELP REPAIR MUSCLES CARBS WILL RELOAD THE MUSCLE GLYCOGEN

- CARB UPTAKE AT IT’S HIGHEST (WE THINK)

- FATS SLOW DOWN THE ABSORPTION

CARBS ONE HOUR AFTER RACE

- CHO:PRO – 2:1 0R 3:1 RATIO

- FATS CAN BE INCLUDED

- GOOD TIME FOR A HEALTHY, EASILY DIGESTED MEAL INCLUDE SALTY FOOD